# When OKRs work

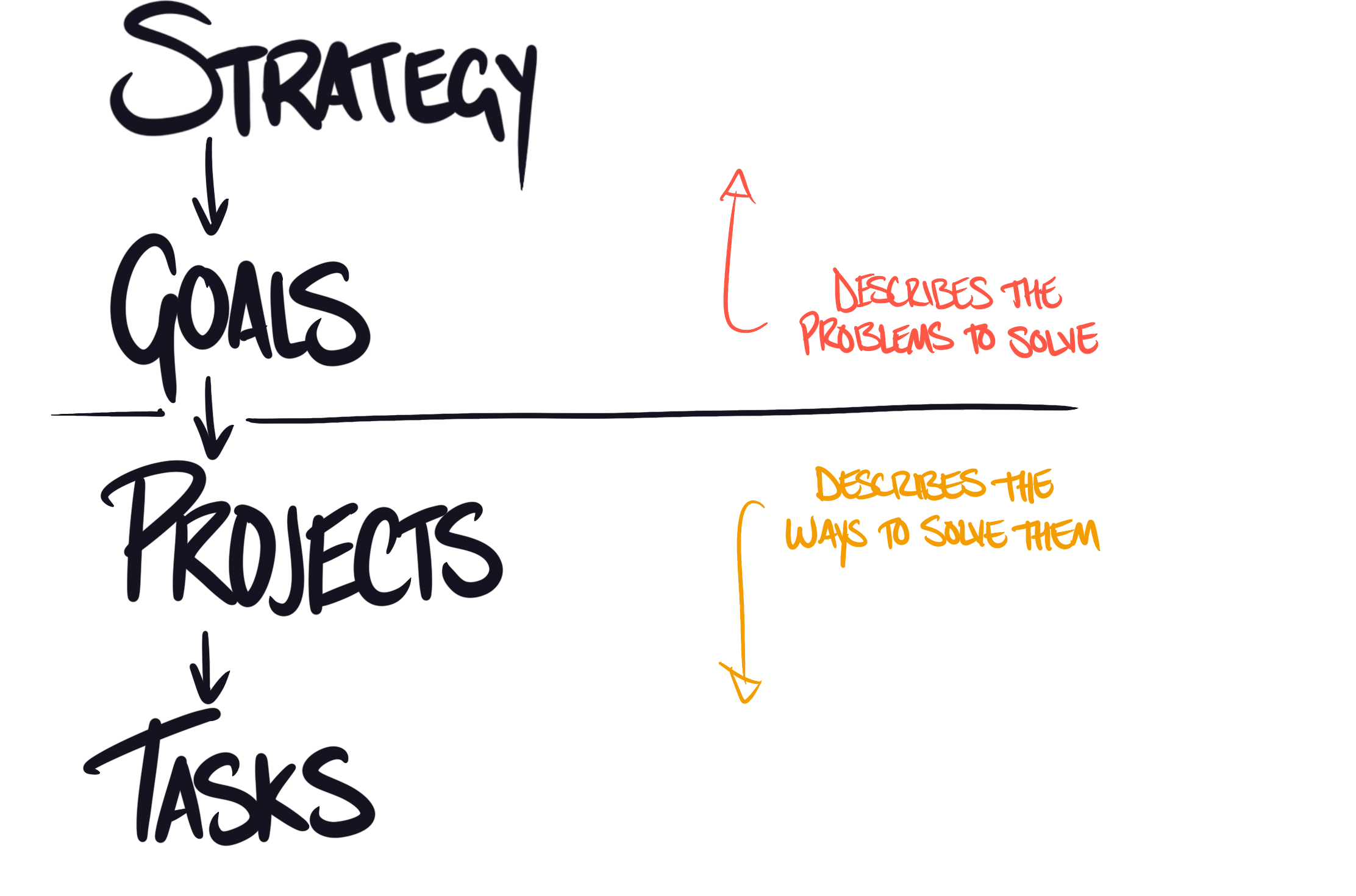

Every organization needs to communicate direction at four levels:

Strategy:

"A computer on every desk and in every home." High-level vision that shows where you're going but not how to get there.

Goals:

"Increase computers in schools by 20% in two years." Specific problems to solve right now, with clear metrics and timelines.

Projects:

"Launch education-focused marketing campaign." The actual work you'll do to achieve goals.

Tasks:

"Call Jimmy in Marketing." Atomic work items that build projects.

Most frameworks try to handle all four levels. OKRs only handle one: goals.

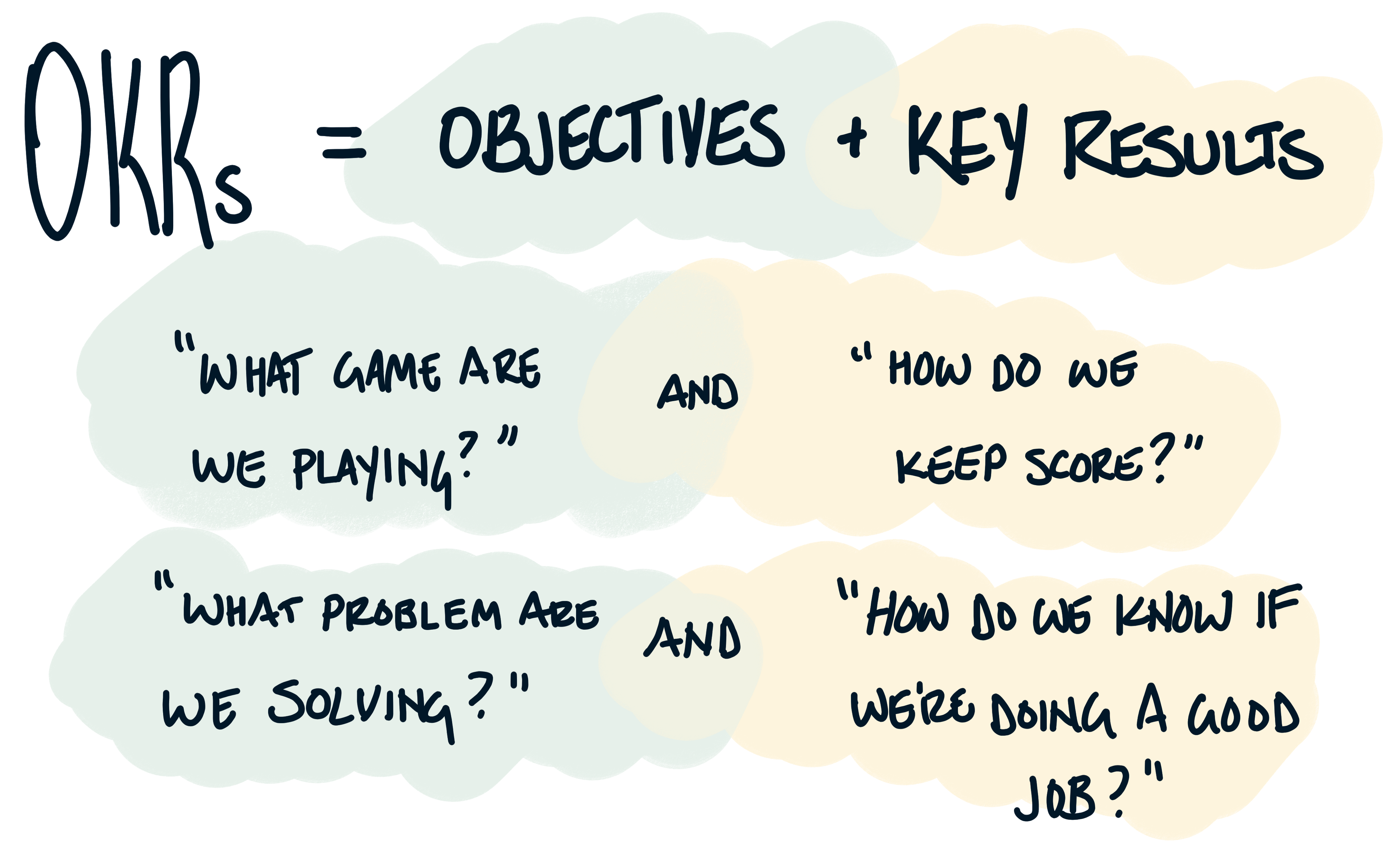

## Why OKRs are different

OKRs are problem-focused, time-bound, and measurable. They communicate goals exceptionally well because goals share these exact characteristics.

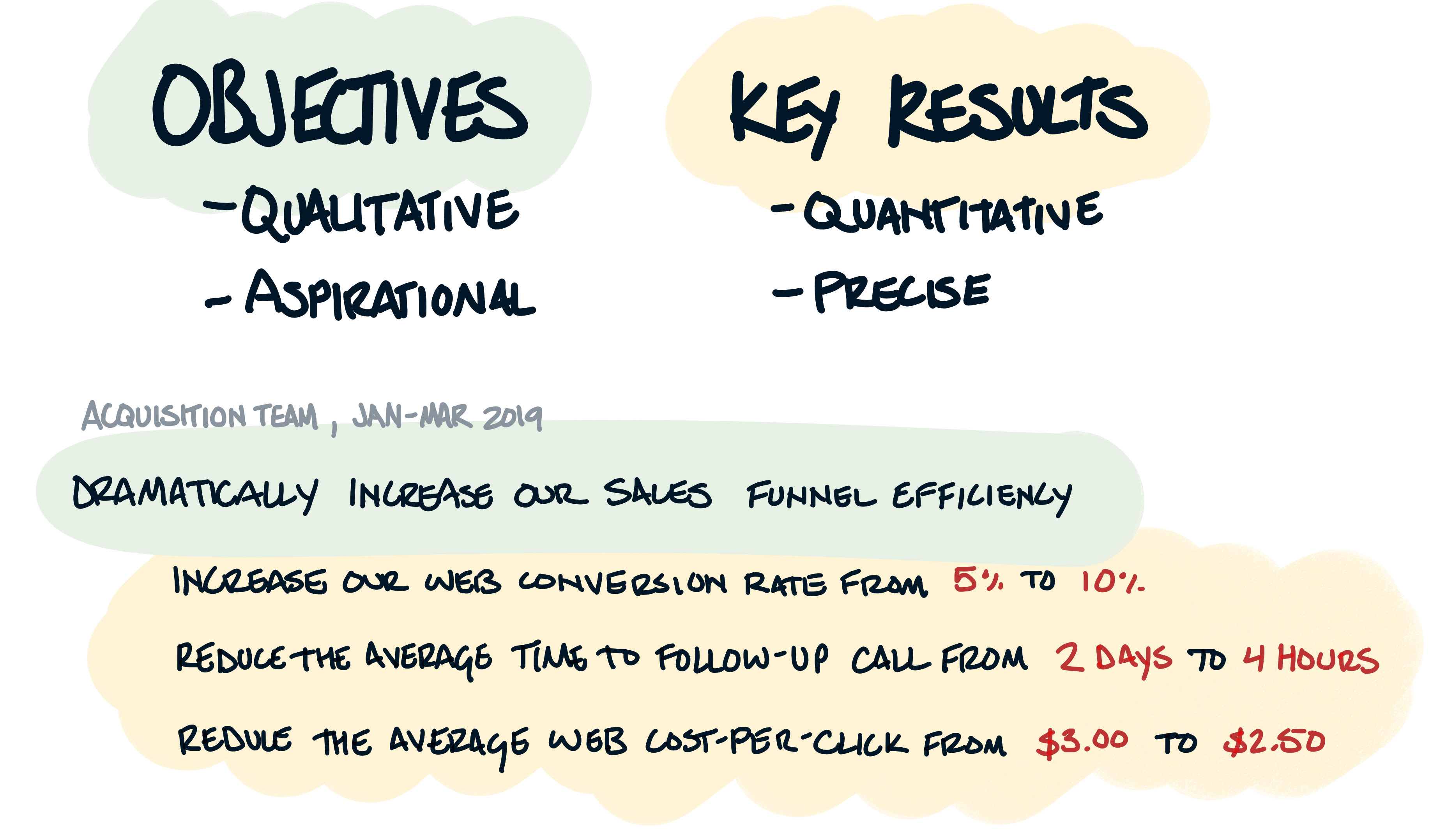

Objectives define what you're trying to accomplish (qualitative).

Key Results measure if you're succeeding (quantitative).

This OKR works for three reasons:

- →Clear problem focus. It's qualitative and aspirational but leaves questions that Key Results answer: What part of the funnel? What counts as "dramatic"? How do you define efficiency?

- →Cross-functional alignment. Sales funnel efficiency isn't one team's job—it requires marketing, engineering, and sales working together.

- →Time-bound urgency. The deadline forces you to find a piece of the problem you can solve right now, not eventually.

## Using OKRs at scale

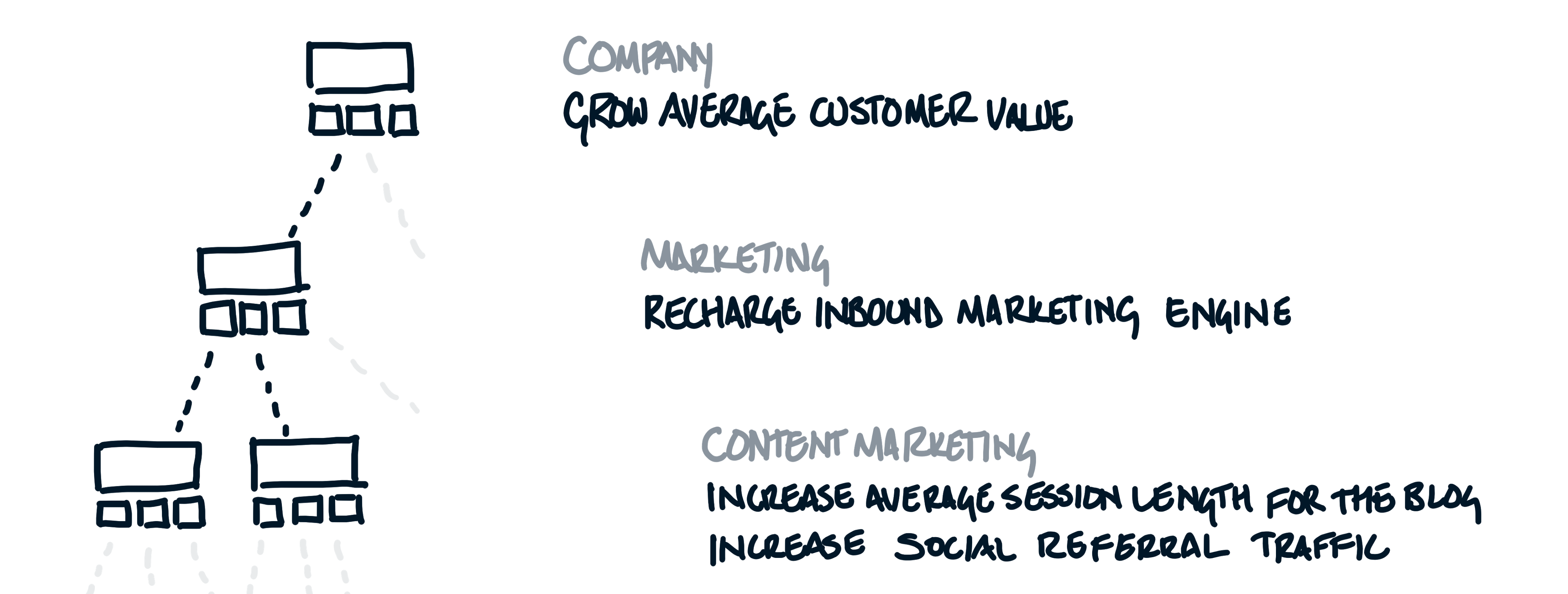

### Hierarchy

OKRs can work at every organizational level. Company OKRs give overall strategy. Department OKRs refine company goals. Team OKRs tackle manageable pieces.

But don't stack them rigidly. Loose alignment is better than tight coupling. Like earthquake-resistant buildings, small gaps between levels provide flexibility when things change.

### Self-determination

OKR-setting is always a two-way conversation. Leaders share high-level OKRs with teams. Teams set their own OKRs and share them back.

Lower-level teams have more context and better ideas about how to solve problems, you should let them propose their own goals that align with yours. Leaders who dictate OKRs handicap their teams and become bottlenecks.

### Difficulty

OKRs should be difficult, not impossible. Teams should aim slightly beyond what they think they can deliver.

If teams are setting bold goals, they'll achieve around 70% of them. The target is always 100%, but life happens and 100% is rarely possible. 70% is a feedback loop on how challenging your OKRs were. If you only achieve 30% they were probably too hard, if you achieve 100% they were probably too easy.

### Review process

Review OKRs regularly but don't tie them to performance management.

Never tie OKRs to promotion or compensation. This encourages sandbagging—setting easy goals to look good rather than bold ones that drive progress.

Use OKRs for alignment, transparency, and feasibility feedback. Use separate processes for performance evaluation.

OKRs are easy to do wrong. But if done right, they can be a great tool for organizational alignment.