# Organizational entropy

Every business begins with clean lines. At the start of a new venture or project, everyone knows exactly what they're responsible for. The developer writes code, the designer builds interfaces, and the product manager sets priorities. Boundaries are clear, decisions flow smoothly, and work gets done.

But this clarity doesn't last.

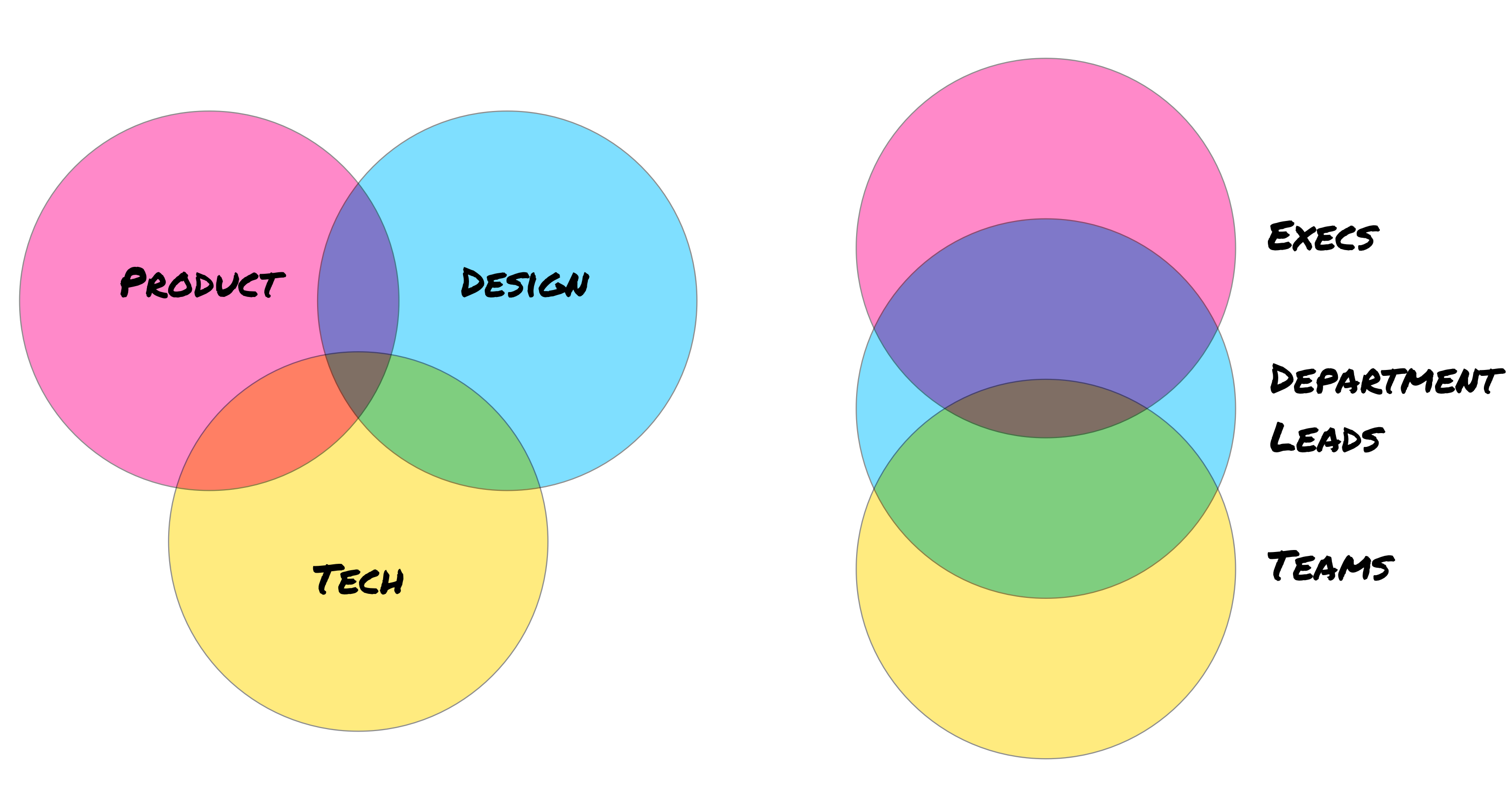

Over time, these crisp organizational lines begin to blur. You hire a developer who studied design and has strong opinions about user experience. You bring on a designer who loves diving into data visualization and is an expert with graphing libraries. You recruit a product manager who used to be a data architect and can't help but optimize the engineering stack.

This cross-pollination of skills often creates value. Multi-disciplinary team members contribute beyond their core expertise, bringing fresh perspectives and reducing the friction that comes from rigid silos. Work environments where people "stay in their lane" aren't just inefficient—they're often stifling to talented people who want to grow.

But there's a hidden cost to this flexibility. When talented people contribute across disciplines, it becomes harder to know who makes which decisions.

Consider these scenarios:

- →Does the ex-designer product manager make UI decisions, or does the data-visualization-loving designer?

- →What if you're building a metrics dashboard instead of a marketing page—does that change who decides?

Each time someone steps outside their formal role to contribute, they create a subtle connection between departments. These connections start weak—perhaps a developer offers design feedback, or a designer writes some basic SQL queries. But as these informal contributions accumulate, the connections strengthen. They begin to act like organizational rubber bands, slowly pulling once-distinct roles together.

Imagine a developer who designs and builds a new user interface. The next time someone wants to modify that interface, they naturally pull in the developer to discuss the original decisions and reasoning. Because the developer has all the context, they get invited to the next design discussion. And the next one. Before long, they're involved in every design decision, functioning as a de facto designer while officially being an engineer.

This pattern repeats constantly across growing organizations. As these informal connections multiply and strengthen, functional areas that were once clearly separated begin to overlap. The overlaps create confusion about ownership. When multiple people could reasonably make a decision, often no one does. Decision-making slows, then stops.

Left unchecked, this dynamic resolves in one of two ways, both equally destructive:

- →Paralysis through politeness: No one feels empowered to make decisions because they don't want to step on someone else's toes. Progress grinds to a halt.

- →Chaos through collision: Everyone tries to make the same decision simultaneously, often in opposite directions. Progress grinds to a halt.

In either case, work becomes unnecessarily difficult. Teams spend more time talking about decisions than making them. The word "consensus" gets thrown around constantly. Velocity drops dramatically—frustrating for large companies, potentially fatal for startups.

This phenomenon follows what I call the Law of Organizational Entropy:

Roles and responsibilities drift toward sameness unless acted upon by an opposing force.

This law operates universally. It affects every organization, creating drag both horizontally across teams and vertically between management levels. The larger and faster-growing the organization, the more pronounced the effect becomes.

Fighting organizational entropy requires intentional action. The solution has two parts: first, defining how things should work, and second, anchoring those definitions to your actual processes and tools.

## Define How You Work

Most leaders understand the importance of vision—they invest heavily in product roadmaps, north star metrics, and strategic plans. These tools show teams what they're working toward. But they only tell half the story.

Teams also need to understand how they should work together.

In software development, we use a "main" branch as the canonical version of our codebase. This branch represents the team's current, working state. Individual developers can branch off to experiment with new features or approaches. If their experiment succeeds, they merge it back into main. If it fails, they can always reset to the known-good state of the main branch.

Publicly defining how your team should work creates the same kind of safety net for organizational practices. It allows teams to experiment with new ways of collaborating while maintaining a clear reference point. If an experiment creates confusion or conflict, everyone knows how to get back to a functional state.

When everyone understands that the tech lead owns code quality in development while the product manager owns anything that ships to users, you eliminate a host of potential conflicts before they start.

But defining these standards requires careful judgment. Pick the wrong aspects to standardize, or standardize too much or too little, and you can create more problems than you solve.

The teams living with your guidelines will tell you whether they're helpful or harmful. Talk to them regularly. Ask whether your ideals feel right or need updating. Process is a moving target. What feels "right" changes as organizations grow and evolve—build systems that can adapt.

For an excellent example of this in practice, look at Intercom's approach in their piece Lessons learned from scaling a product team. Notice how they emphasize that their process continuously evolves—yours should too.

## Find Your Anchors

One of my favorite examples of elegant organizational anchoring comes from Facebook's early mobile transition.

When Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook was going "mobile first," he expected immediate change. But weeks later, he found himself in the same meetings, listening to the same people discuss the same desktop-focused priorities. Declaring change wasn't enough to create it—even as a CEO.

Faced with this reality, Zuckerberg made a drastic decision. He announced that he would no longer attend meetings, review ideas, or look at prototypes unless they were mobile-focused. He cleared his calendar completely and stuck to his commitment.

The initial chaos was intense. But it turns out that having the CEO refuse your meeting is highly motivating. Within days, his calendar started filling up again. Every single meeting was now about mobile.

Within months, the entire company had shifted focus. Zuckerberg found a way to anchor his desired change into the company's daily routines, creating dramatic results.

Zuckerberg anchored change through his calendar, but there are countless other options. Every organization has routines, cadences, and rhythms that govern how work gets done—daily standups, weekly reviews, monthly planning sessions, quarterly business reviews. The key is finding ways to hook your desired behaviors into these existing routines.

Successful anchors make it easier to work the "right" way than the "wrong" way.

Want teams to do more user research? Schedule recurring sessions where their boss's boss reviews the latest findings. You'll see user research left and right.

Want to improve how your company sets goals? Add a goals section to your budget request template. Reject any requests without properly completed goals. Every team's objectives will suddenly become much clearer.

Finding the right anchor points can be challenging. Start by looking where different functions or management levels intersect—those handoff points often have meetings, templates, and communication pathways that you can modify. Intercepting and adjusting these information flows creates powerful leverage for change.

Organizational entropy is natural and unavoidable. It's a byproduct of growth, and it becomes more pronounced as companies scale quickly. But with thoughtful planning and precise action, you can keep it in check. The alternative—letting roles blur and decisions stall—will slowly strangle your organization's ability to execute.

The choice is always yours to make.